Research Designs Review

Psycholoy and Child Development

Big research families

| Quantitative | Qualitative | Mixed Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental designs | Narrative Research | Convergent |

| Non-experimental | Phenomenology | Explanatory sequential |

| Longitudinal Designs | Grounded Theory | Exploratory sequential |

| Ethnographies | Complex designs with embedded core designs | |

| Case Study |

Big research families II

Survey research: provides a quantitative or numeric description of trends, attitudes, or opinions of a population by studying a sample of that population. It includes cross-sectional and longitudinal studies using questionnaires or structured interviews for data collection—with the intent of generalizing from a sample to a population.

Experimental research: seeks to determine if a specific treatment influences an outcome. The researcher assesses this by providing a specific treatment to one group and withholding it from another and then determining how both groups scored on an outcome.

- True experiments

- Quasi-experiments

- Single-subject designs

Big research families III

Qualitative designs

Narrative research: The information retold or restoried by the researcher into a narrative chronology. Often, in the end, the narrative combines views from the participant’s life with those of the researcher’s life in a collaborative narrative

Phenomenological research: the researcher describes the lived experiences of individuals about a phenomenon as described by participants.

Grounded theory: is a design of inquiry from sociology in which the researcher derives a general, abstract theory of a process, action, or interaction grounded in the views of participants.

Ethnography: is a design of inquiry coming from anthropology and sociology in which the researcher studies the shared patterns of behaviors, language, and actions of an intact cultural group in a natural setting over a prolonged period of time.

Case studies: in-depth analysis of a case, often a program, event, activity, process, or one or more individuals.

Let’s focus on causality for a while

What is first A or B ?

- Causality means that we would expect variable X to cause variable Y.

- For example: Does low self esteem cause depression? How do we know?

Let’s take a look at some spurious correlations:

Experiments help us!

Can we know if A causes B with a survey?

Can we know if A causes B conducting an experiment?

We can manipulate a variable and observe what happens afterwards, but it is good enough?

Do we need something more on our design?

Experiments help us! II

- Pure experiments need a control group to account for counterfactual information, this also helps to rule out possible confounding variables.

- Example: how would you measure the effect of physical activity on cardiovascular fitness? What would be a good experimental design?

Can we assume causality in survey designs ?

- In survey designs we cannot manipulate the independent variable, but some researchers claim that is possible to make causal inferences when you conduct a longitudinal study.

- In longitudinal studies you satisfy the temporal requirement, you could evaluate if X = independent variable happens before Y = dependent variable.

- For instance: You could measure a baby’s weight every month and evaluate how many times the baby is breastfed. But, do we need counterfactual information?

But we haven’t defined cause, and effect

Shadish et al. (2002) :

- Let’s try an example, consider a forest fire:

- Multiple causes: match tossed from a car, a lightning strike, or a smoldering campfire

- None of these causes is necessary because a forest fire can start even when, say, a match is not present. Also, none of them is sufficient to start the fire. After all, a match must stay “hot” long enough to start combustion; it must contact

combustible material such as dry leaves. We also need oxygen!

But we haven’t defined cause, and effect II

- A match can be consider part of multiple causes, therefore we can call it a “inus condition” (Mackie, 1974, p. 62) “an insufficient but nonredundant part of an unnecessary but sufficient condition” to cause a fire.

Shadish et al. (2002) :

- It is insufficient because a match cannot start a fire without the other conditions.

- It is nonredundant only if it adds something fire-promoting that is uniquely different from what the other factors in the constellation (e.g., oxygen, dry leaves) contribute to starting a fire. It is part of a sufficient condition to start a fire in combination with the full constellation of factors. But that condition is not necessary because there are other sets of conditions that can also start fires.

Important

Many factors are usually required for an effect to occur, but we rarely know all of them and how they relate to each other. This is one reason that the causal relationships we discuss are not deterministic but only increase the probability that an effect will occur.

But we haven’t defined cause, and effect III

What is an effect?

- An effect is better define if we have a counterfactual model.

- A counterfactual is something that is contrary to fact.

- In an experiment we observe what did happen when people received a treatment.

- The counterfactual is knowledge of what would have happened to those same people if they simultaneously had not received treatment. An effect is the difference between what did happen and what would have happened.

Important

We could add a group of participants to a waiting list, do you have any example in mind?

Let’s finally define causal relationship

Shadish et al. (2002) :

- This definition was first coined by John Stuart Mill (19th-century philosopher), a causal relationship exists if:

- The cause preceded the effect.

- The cause was related to the effect.

- We can find no plausible alternative explanation for the effect other than the cause.

Warning

Correlation does not prove causation!!! We will use this as a mantra in this class.

Let’s switch to important concepts

Don’t forget how variable is the concept of variable!

Independent variable

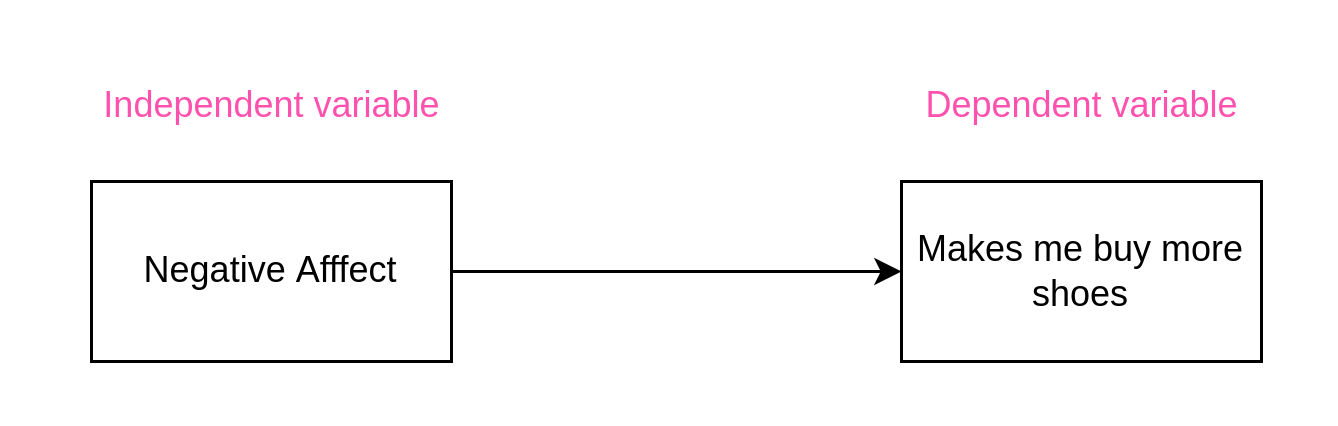

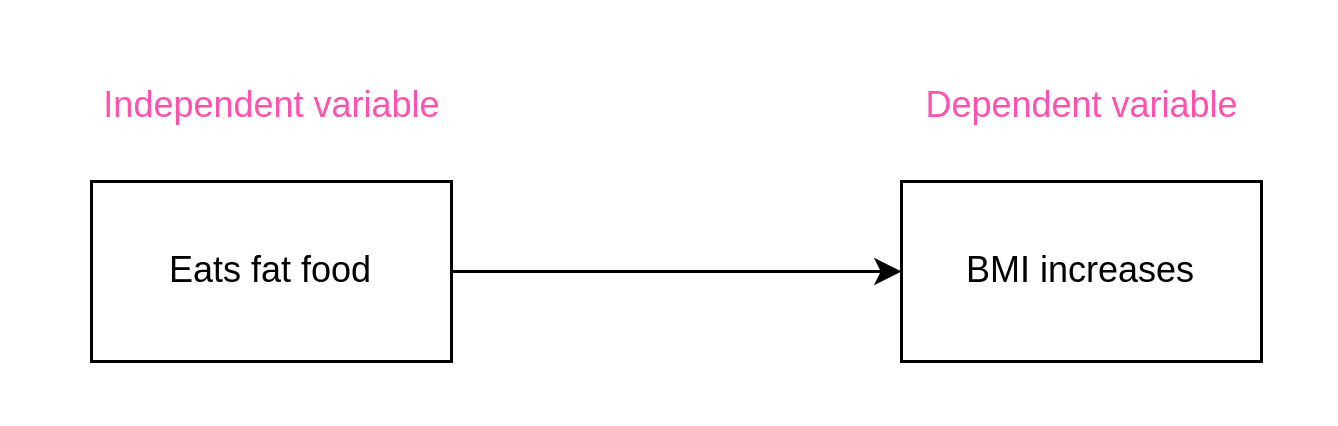

- Independent variables: are those that influence, or affect outcomes in experimental studies. They are described as “independent” because they are variables that are manipulated in an experiment and thus independent of all other influences.

- However, we will use this concept more vaguely, we won’t use it only when talking about experiments. It will be used also for correlational relationships, formally its name in survey designs is predictor.

Dependent variable

- Dependent variables: are those that depend on the independent variables; they are the outcomes or results of the influence of the independent variables. It is also called outcome in survey designs or correlation designs.

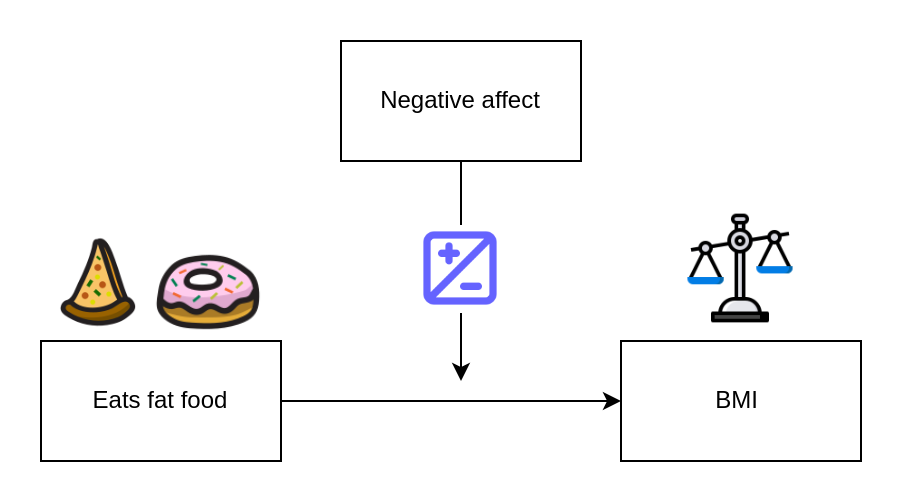

Moderating variables

Moderating variables are predictor variables that affect the direction and/or the strength of the relationship between independent and the dependent variable.

Mediating variables

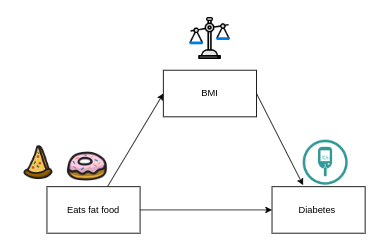

- Mediating variables stand between the independent and dependent variables, and they transmit the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable.